nature trip to costa rica

July 2023

Map of Costa Rica with all the places visited

(extracted from birding app eBird (see link at the end of the report))

Sorry I was too lazy to make my own one (we visited so many places)

Introduction

Finally, back to the tropics! After my visit to Costa Rica in 2018, I was looking forward to search for animals again in a tropical rainforest environment, and finally this 2023, with the COVID pandemic now over, it has come to fruition. And why back to Costa Rica instead of going somewhere else? Well, I'm not going to deny that I really want to visit the splendid rainforest of southeast Asia, tropical Africa, Australia or the Amazon, with the amazing animal life they host. But, any trip to a new place needs a careful study and preparation. You need to know the animals that you are going to see, select the target species and then look for the best places to see them, planning the trip route and the logistics. All of that needs a lot of time, which unfortunately I haven't had much of this year. However, I didn't want to give up a trip in the summer, so when my friend Ángel Gálvez suggested the idea of returning to Costa Rica, I didn't think it was a bad plan. On my previous trip with Max Benito, we were still students with little money, and although we saw many incredible species, there were still many more to see, some of them among the most emblematic. Now, with a slightly better budget and more knowledge on the ground, we have been able to dip more inside country and its wildlife. The team was completed with Iván Alambiaga, Ángel's friend and like me also an avid birder, thanks to which we were able to focus a little more on birds than last time, seeing some much desired species for me. In addition, we have a fourth biologist in the team, Carlos Ortega, who also joined me on my last trip to Morocco, and like Ángel is a member of the Timon Herpetological Association we have in Valencia. Carlos joined the team except for the last days because of his need to work (damn it!).

The trip covered much of the parts of the country that I did not see on my first visit, with only one place repeated. In the 20 days of the trip, this time with a rented car (last time we used buses), we were able to visit most of the main representative ecosystems of Costa Rica. That resulted in a large number of species, especially amphibians, reptiles and birds, which are the groups we were most eagerly looking for.

In terms of photography, I took better equipment on this trip than on my previous visit to the country. My already worn out Nikon D7100 camera, but still holding up, with the Tamron 90mm VC macro and the Tamron 150-600mm G2 telephoto lens (plus flash, difuser, etc.). But also, for those animals that you feel too lazy to mount a reflex camera (you know), I took an Olympus TG-6 compact camera, which was also useful for photographing animals on rainy nights, as it was submersible. So, you will clearly see two qualities in the photos of this trip report, but I don't think it will be something that will bother you.

The four jungle explorers posing under a waterfall after an uphill hike over an erupting volcano.

From right to left: Carlos Ortega, Iván Alambiaga, Ángel Gálvez and me (Luis Albero)

6-7 July: Barva and Poás volcanoes

Except for Carlos, we took our flights from Valencia with a brief scale on Colombia which didn't allow us to do any herping or birding (except to see one lifer pigeon from the airport window). This time I was a little less sleepy as I slept better on the planes than on the 2018 trip. Once in Costa Rica, we joined with Carlos and our guide for the first two days, Esteban Arrieta. Esteban has a great knowledge of all Costa Rican herpetofauna and especially of the mountain areas surrounding the central valley, where his help would be essential to find our first targets. Thus, we would start our trip in an atypical way, through medium and high mountain cloud forest ecosystems in the Poás and Barva volcanoes. Our targets here were two species of pit vipers and a leaf frog that neither Angel nor I had seen on our previous trips and were a big pending account. But before starting the night herping, as we had told him that we also wanted to see birds, Esteban took us for lunch to a beautiful place (Soda Cinchona) with hummingbird and other bird feeders where we were able to see numerous species, enjoy the meals and make lifers. Among the species seen,I would highlight the violet sabrewing, the largest hummingbird in the country, as well as the two species of barbets found in Costa Rica. It was a great place as a starter for the trip!

Once it got dark, Esteban drove us to some coffee plantations near the forest, where we also met another local herping guide, Cristian Porras, and his client from the US, Lou Boyer. There we were able to see our first herpetological target, the golden-eyed leaf frog (Agalychnis annae), which were on heat so we could enjoy their calls and see both males and females. This species suffered a sharp decline in previous decades, like many amphibians, but lately it seems to be recovering and new populations are appearing. An oustanding frog. The second half of the night we drove to a near stream to look for the side-striped palm pitviper (Bothriechis lateralis). It took longer than for the frogs, but finally the sharp eyes of Esteban found one still on low branches, high above a slope. I thought this snake was one of the most beautiful snakes of the trip, as a fan of arboreal vipers myself, with its intense green color and its already considerable size, although they can grow bigger from what we were told. The pity was that it started to rain heavily so we couldn't take very good pictures of it, but the important thing is always to see the animal!

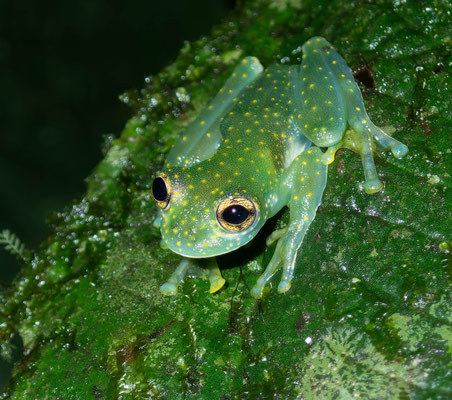

After spending the night in a rustic hut in the middle of the mountain, the next day we set out to look for the second of the target snakes, the black-speckled palm pitviper (Bothriechis nigroviridis). This is a rather more difficult species to find, which is not always seen on herping trips to Costa Rica. However, Esteban was monitoring a cattle area where it had been seen recently, and after a little more than an hour of searching, our guide again found a beautiful juvenile specimen camouflaged in the moss. A real beauty of an animal, perhaps my favorite snake in Costa Rica, which we were able this time to enjoy and photograph to our heart's content. In the evening, we visited the area again in case any other larger Bothriechis appeared, or other vipers present in the area but even rarer, such as the Cerrophidion sasai or the Atropoides picadoi. But we only saw some amphibians, at least some new species for me, such as the meadow tree frog (Itsmohyla pseudopuma). We heard a lot of the bromelian-breeder Itsmohyla picadoi, but despite the efforts of Esteban was not possible to see one.

Black-speckled palm pitviper (Bothriechis nigroviridis)

8-11 July: Guanacaste

The next destination in our trip was the driest part of the country, the province of Guanacaste. After saying goodbye to Esteban and picking up the rental car, we began the first of the long drives to the Santa Rosa National Park area, in the extreme northwest of the country, close to the border with Nicaragua. This area, as has been said, is the driest and has a savanna-type environment where different species thrive than those in the rest of the country, such as the Central American rattlesnake (Crotalus simus), perhaps our main target here. We stayed in a humble but cheap hostel next to a river, where one night we saw crocodiles, and we started with a walk through its gallery forest where, in addition to some iguanas or basilisks, we were able to see the largest of Costa Rica's owls, the incredible spectacled owl (Pulsatrix perspicillata). In this part of the country, roadcruising on tha night is the best way to find snakes, and we spend most time doing it, but also did some active searching when we got tired of driving. On the first night, in a road close to Santa Rosa we found some new snakes, the best one was the central american coralsnake (Micrurus nigrocintus). Thus I achieved one of my main reasons to come back to Costa Rica finding my first ever coralsnake, and was even more beautiful (and defensive) that I expected. I would also highlight my first frog from the Microhylidae family, with that funny appearance of its short mouth, Hypopachus variolosus. This first night we also saw some medium-sized american crocodiles in a stream, where I tried to look for the extremely difficult "cantil" (Agkistrodon howardgloydi), CR's most difficult venomous snake, of course without any luck. On the end of the night, we did some active searching near the hostel, finding a big lyre snake (Trimorphodon quadruplex), with some prey inside.

It was thus a great first night of herping in Guanacaste, in spite of not finding our main target, the rattlesnake. The following morning, we went to see some coastal landscape around Santa Rosa, doing some birding and daytime herping and at the same time looking for promising roads for the night. We could enjoy some nice birds, like frigatebirds and pelicans, very common here but an exotic view for europeans like us. We also saw some colorful lizards, giant kingfishers and even a racoon, after having dinner and preparing for the night. That night we did some new roads but find similar species than the night before, like another coralsnake. But we also saw some very interesting mammals (most of them were unable to be photographed), like one coati (Nasua nasua), grey fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), the always funny opossums (Didelphis marsupialis), a skunk (Spilogale angustifrons), and even a coyote pack (Canis latrans).

The last full day in Guanacaste we did a hike around Santa Rosa NP seeing lots of birds, like the beautiful long-tailed manakin. On the night it was our last chance to see the rattlesnake and other snakes typical of Guanacaste. We started on a road near the other National Park of the region, Palo Verde. There, we found another, big lyre snake (+180cm) and one of our most desired species, the slender hognose pit viper (Porthidium ophryomegas). Then we moved to the roads visited the night before, and did also some interesting finds, like a kingsnake (Lampropeltis abnorma) and another, more contrasted, Porthidium. However, no rattlesnake this time, it seemed that the very dry conditions, even on the rainy season (due to "El Niño" fenomena), had made snake activity to be lower than expected. Therefore, I will have to wait for my next trip to the Americas to see my first rattlesnake, one of the great unfinished business from this trip to Costa Rica.

As we wanted to try new ecosystems and species, the following day we headed to the Guanacaste volcanic cordillera, to "Rincón de la Vieja" National Park, in the volcano with the same name. It is one of the most active volcanoes in Costa Rica, with more than a hundred eruption events in the first half of 2023. But at the same time it host a well preserved premontane forest with different bird and even herp species (such as jumping pit vipers), that we wanted to give a try. As we roadcruised a lot the night before, we arrived at mid morning and started a long hike towards a waterfall in the volcano slope. It is important to note that, in these tropical areas, most bird activity is usually very early in the day, with the peak from dawn until about two to three hours later. From then on, activity drops sharply and in the central hours it is very difficult to see birds. This makes it difficult and tiring to combine the night-time herping with early morning birding, which would be a constant throughout the trip. In spite of not being at the best hours we saw some interesting birds on the hike. One of my favorites was the pale-billed woodpecker (Campephillus guatemalensis), biggest woodpecker in Central America and a relative of the mythical, now sadly extinct, imperial woodpecker. Also, we had nice views of spider and capuchin monkeys. Being on daytime, we did not saw many herps on the place, at least not new species. The anecdote of the day was that, as we climbed towards the waterfall, we began to hear loud noises that at first we thought were thunder, as it was quite cloudy and raining at times. However, as we descended from the waterfall we could see a large plume of smoke rising from the crater of the volcano. It had indeed erupted. Although it was quite far away and probably not dangerous, it was the only time during the trip that Carlos, running down the slope, took the lead. At night we took dinner in a more decent restaurant (the last days we almost exclusively ate rice and beans), and did a final roadcruise but without much success due to the strong wind.

12-13 July: Caño Negro region

Finally, we abandoned Guanacaste, having seen a number of very cool species, despite missing some of our main targets. Our next destination was more focused on birding, as we headed towards one of the most important wetland system in Costa Rica, the Caño Negro wetland. It took us all day to get there from Santa Rosa, with a little stop at Heliconias, a place with foothill forest when we did a little birding hike, without much success due again to not being on the best time of the day, but we could add some lifers. The forest landscape was great and they have some canopy bridges which was also a new and exciting experience, to see the rainforest from above. We even find one active snake there, a diurnal Dendrophidion apharocybe.

We arrived in Caño Negro at night, after some stops to look at singing frogs and even seeing one of those strange nocturnal birds that look like sticks, a common potoo. Once in the cabins we booked for the night, we met met the kind owner, it was a curious thing that she was scared of toads. And that is truly a problem having literally your yard infested with big cane toads (I counted more than 20 in only one look with the flashlight). Anecdotes aside, the next day we woke up very early to meet our guide Renato Paniagua, from the company Caño Negro Experience, at the pier to enjoy a morning boat tour on the wetland. One of our main targets here, on terms of birding, was the beautiful agami heron (Agamia agami), for many the world's most beautiful heron. In spite of having a big distribution in the neotropics, this species is always elusive and rare to see, being Costa Rica and Caño Negro one of the best places to find them. In addition, here many typical waterbirds of neotropical areas are present, and not only birds, at it harbors also the biggest caiman population of the entire Costa Rica.

We thus begin the tour with very good expectations. And very soon we started to see the first birds, thanks in large part to Renato's incredible knowledge of the wetland and its inhabitants, as he knew where each species was and how to recognize their vocalizations, which made everything easier. We enjoyed it so much that the five hours we had booked turned into six and a half, visiting every corner of the wetland. It was undoubtedly the day of the trip that we were able to see more bird species, more than 80, such as the beautiful anhingas, the sungrebe, and difficult species such as the yellow-tailed oriole or the nicaraguan grackle. We also saw all the kingfishers of the American continent except for one species. As for our target, the agami heron, it was a bit of a struggle at first, but Renato had the best spot up his sleeve for last, and in the end we were able to enjoy up to four specimens, adults and juveniles, of this spectacular bird. Herpwise, we saw emerald basilisks, iguanas and tons of spectacled caimans, some of them very close.

Agami heron (Agamia agami)

After ending the tour with a very good hype, we thanked Renato and abandoned Caño Negro heading towards our next destination on the Caribbean slope. On our way we go trough some open fields in the outskirts of Caño Negro where we sum some more interesting birds, such as a quite far jabiru (a massive bird, biggest stork in the Americas). We also enjoyed an spectacular great potoo in a tree that Renato told us, the thing was that the tree was next to a house, and the woman that lived there didn't like much the spontaneous birders on her backyard... We arrived at night to our destination, Centro Manú, near Guápiles, to begin the "crazy Caribbean herping" part of the trip.

14-16 July: Centro Manú

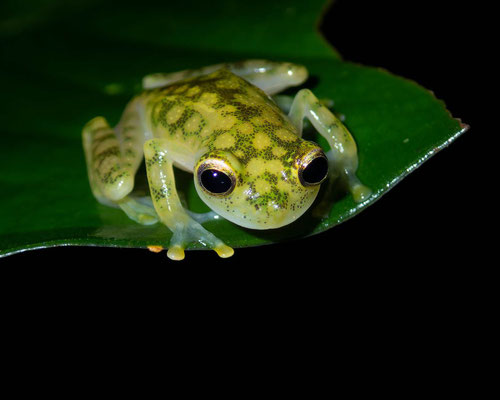

Once in Centro Manú, we met with Kenneth Gutierrez, worker of the center and also an avid herper and herping guide. Once we had settled in and despite the accumulated tiredness of the trip, we were looking forward to a night walk through this piece of advanced second growth Caribbean forest. We consulted Kenneth about the local trails and set off. Soon, the explosion of life in these tropical rainforests became noticeable, and it didn't take long for a couple of amphibian species to appear that I had missed on my previous trip and had been keeping an eye out for. The first, a leaf litter toad (Rhaebo haematiticus), a curious species of bufonid with contrasting coloration. But the target species that had made us choose Manú as our Caribbean destination showed itself soon after: the spectacular crowned frog (Triprion spinosus). A true iconic species among Central American amphibians, only to see this big tree frog was reason enough to come back to Costa Rica. Another species found here is the beautiful salamander Oedipina carablanca, which we tried to find every night but is a difficult animal and due to the dry conditions we do not succeed. Back to our first night, continuing the night walk, we found another iconic Costa Rican species, the venomous terciopelo (Bothrops asper), a subadult just curled in the middle of the path, typical. After a few more snakes and frogs along the pleasant route, we returned to the cabin to rest, not too much, as Ivan and I intended to get up early to see the local birds.

The following morning, thus, we got up a bit early and went to see some birds around the station. As usual, it was tricky to see birds on the dense rainforest, but some interesting lifers showed up, like the charismatic white-collared manakin (Manacus candei), of which we saw a male on its lek doing the nuptial dance. Later on, when I was birding in another part of the center, Carlos came and told me that, after taking a photo of a bird, he had seen a large viper in the photo (he wasn't sure if it was a large Bothrops or even a Lachesis) and to go back to the area and see if we could spot it before it was too late and it was gone. Heading there, near the path just out of the center we saw the body of an impressive very big terciopelo (more than 1.8 m) inside some bushes. It was too big for handling it safely with our snake hooks so Carlos went to the cabin to get the snake tongs we brought for this situations and to tell the other two as I watched over the snake. So we were finally able to capture it and enjoy it for a few minutes before releasing it again. Quite a snake, the biggest viper I had ever seen and with a temperament to match. In the excitement of the moment, no one brought me my cameras so I could only take pictures with my mobile phone, but I didn't mind too much having enjoyed this madness of an animal.

As the evening drew in, we were able to meet two more local herpers, Diego Ugalde and Ashley Torres. I had been in contact with Diego on the recommendation of my friend Max, who had been with him in the Amazon, and finally we were lucky enough to meet up on this part of our trip to do some herping. After meeting up with Kenneth who was our guide for the night, we headed first to a nearby pond where there was a frenzied activity of different species of amphibians. Among them, two species of pelomedusid frogs, the most iconic red-eyed tree frog (Agalychnis callydrias), that Carlos and Iván saw for their first time, and its rarer and a bit duller counterpart, Agalychnis saltator. Around the pond we could also see two eyelash pit vipers (Bothriechis schlegellii), third species of Bothriechis for the trip and another iconic Costa Rican species, with greenish coloration. After enjoying herping around the pond we headed into the jungle, taking some trails that Kenneth knew. When we were crossing a small stream I saw a suspicious eyeshine above some branches, which turned up to be a ghost glass frog (Sachatamia ilex). This is perhaps the most spectacular of Costa Rican glass frog due to their striking eyes. I saw only one individual in my last trip and was under a heavy rain, so it was nice to see it again and take better pictures.

After crossing the stream over a non-very-reliable-looking hanging bridge, Diego found another longly desired species for me, a Costa Rican coralsnake (Micrurus mosquitensis), my second coral snake species. This is a more brilliantly colored coral snake than the ones we saw on Guanacaste, and I enjoyed it so much, in spite of being difficult to take good photos due to its nervous behavior. We continued our journey through the forest, and the night was still lively as another of the objectives of the trip appeared for me, the rainforest hognosed pitviper (Porthidium nasutum), with a rather unusual and blurred pattern that delighted even the local herpetologists. But the night still held one last surprise, even for Kenneth himself who knows these rainforests so well. For we briefly heard a powerful call coming from the treetops, which I did not recognise, but Diego and Kenneth confirmed that it was one of the most incredible frogs living in the Costa Rican rainforests, the ones even called for some "marvelous frogs" (Ecnomiohyla sp.). More specifically, it was the species Ecnomiohyla sukia. Ecnomiohyla frogs live and breed high on the trees, which makes this enigmatic frogs extremely hard to see and detect, except for their calls. Although they would be among my favorite frogs in the country, I hadn't count on them for this trip. We tried to look for it on the trees, but it was impossible to see it. In any case, just hearing its song several times in the rainforest environment was a very cool experience for me.

Costa Rican coralsnake (Micrurus mosquitensis)

Rainforest hognosed pit viper (Porthidium nasutum)

Next day Iván and I got up earlier and took the car to go a bit north towards Puerto Viejo de Sarapiquí. There is one of the best areas in Costa Rica to see an emblematic and endangered bird species, the great green macaw (Ara ambiguus). We didn't have an exact spot saved to see them, so once we were in the area we started to drive around. After a bit of exploring we caught a glimpse of the first macaws, but of the other species, the scarlet macaw (Ara macao). We took a different road with a promising landscape, seeing another beautiful bird, the king vulture (Sarcoramphus papa). Finally, a pair of green macaws flew over us very closely, and shortly after we were able to see another perch in some trees a bit far away (pity it was backlit). With the objective accomplished, we had a coffee and food in a local cafe and returned to the Manú.

Back in the place, I did a brief walk on the forest to try to see some new birds, and saw the only three-toed sloth (Bradypus variegatus) of the trip. I also found another jungle jewel, the giant helicopter damselfly (Megaloprepus caerulatus). As a fan of odonata as I am, it was a very cool find to see the world's largest one, they looked almost like a small drone! At lunchtime Keneeth told us about the rosting site of pair owls, so I went there with Ashley and after a bit of searching for this very camouflaged animals we saw them. Another of the coolest owls of Costa Rica, the crested owl (Lophostrix cristata). The day ended with some hummingbirds in the hummer garden of Manú, highlighting a female snowcap hummingbird (Microchera albocoronata), sadly we did not see the iconic male.

The night will be our last on Manú, so we prepared to herp hardly. We joined Diego and Ashley again, and this time we also met a group of local herpers friends of Diego, which doubled the herping power of the team. We began again on the pond where we found similar species than the night before, with up to three eyelash pit vipers. On the stream, we found a new glass frog species for the trip, the cascade glass frog (Sachatamia albomaculata) and a contrasted Porthidium nasutum. We saw more herp species on the forest, some new but nothing very exciting. I took better photographs of one crowned tree frog with my compact camera, that I like more than the ones I took with the reflex of the first one. We also saw some interesting invertebrates, like ambipligians and net casting spiders. We heard again the Ecnomiohyla sukia calling but was also again impossible to see.

Crowned tree frog (Triprion spinosus)

16-17 July: Guayacán de Siquirres

We have reserved one free night on the Caribbean side in case we found an interesting plan outside the places previously booked. After talking to Diego, he recommended us to contact with Greivin, a young man from Guayacán de Siquirres who could take us to a nice area with lots of interesting stuff there. Is a place not far from the C.R.A.R.C., a famous private reserve with lots of herps which I visited back in 2018, but no as expensive. Greivin is not a professional guide but a local with a deep knowledge of the rainforest and how to move and find animals on it, what is called in Costa Rica a "baquiano". So, we leave Manú satisfied with the things seen there and went to pick a hostel on Siquirres city before meeting with Greivin and his brother. This was the hardest herping night of the entire trip and probably also of my life, as Greivin took as on a demanding hike all the night through the forest, of more than 10 Km of paths, streams and even climbing between rocks, cascades and logs. The area is one of the most biodiverse herpingwise of all Costa Rica, with even some sightings of the Central American bushmaster (Lachesis stenoprhys), as well as amphibians such as the splendid leaf frog (Cruziohyla silviae).

We began going to a pond which is the target place to go, in spite there are lots of interesting places on the way. On the first path we found the only vine snake Oxybelis aeneus of the trip. Then we reached the main stream of the area, where we saw an iconic frog, Palmer's tree frog (Hyloscirtus palmeri), another ghost glass frog, and a big ebony keelback (Chironius grandisquamis). We headed to the pond, looking for Cruziohyla near one breeding side Greivin knows, but with no success. The pond was an spectacle of singing frogs, and some snakes where on the hunt near the shores, as a plain tree snake (Imantodes inornatus) and one eyelash pit viper. I found a machete abandoned near the pond and I took it, so that I can better move through the forest looking for animals. It's quite an experience to move through the jungle with the machete, it really increases your ability to get to places, I think I'll try to carry it every time I go into the rainforest.

I wanted to see the stream-dwelling frog Istmohyla lancasteri, so Greivin brought us to a small narrow stream, where this frogs live on the headwaters. Just as we get to the stream, we saw one of our most desired birds, a sunbittern (Eurypyga helias), another iconic neotropical species which usually is difficult to see due to its habitat in streams deep into the jungle. The way through the stream was truly an adventure, going up rocks, felled logs and branches. I even lost my new machete as I climbed over one log, as it fell between branches being impossible to reach. We saw up to four terciopelos on the stream, so you have to be careful where you step! Finally we found a couple lancasteri, a very handsome frog and another missing target from my last trip. We also saw red-eyed stream frog (Duellmanohyla rufioculis), and a couple glass frogs, including Hyalinobatrachium valerioi and H. talamancae, the latter a new species for me. On the way back we found the final animals, like a Oxybelis brevirostris, one Micrurus mosquitensis (no photos as I was tired and it didn't want to pose) and Sachatamia albomaculata on the big stream. We arrived back to the car just on sunrise, very tired we said goodbye to Greivin and headed to the hostel to sleep a bit before heading to our next destination.

17-19 July: Kéköldi indigenous territory

Our next destination was one of the few I had already visited on my previous trip: the indigenous Kéköldi territory, famous for its good options to see the renowned "matabuey" (Lachesis stenophrys). Like the previous time with Max and Rodri, we contacted chief Sebastián, although on this two-night visit we did not see him very often. The station was bustling with activity with a group of young researchers from different countries studying different components of its biodiversity. It has to be said that by this part of the trip we were already pretty tired, especially after the beating in Guayacán, so we took it a bit easy. During the day we did some birding but without killing ourselves too much, especially when Ivan and I were surprised by a strong storm in the jungle kilometers away from the village, and after taking the wrong path several times we returned hours later completely wet...

The night herping was better the second night than the first, although I didn't see anything new compared to the previous trip, except perhaps for the emerald glass frog (Espadarana prosoblepon). That night we were able to see all the vipers in the area, except for the one we were aiming for, despite a lot of effort, in an area of fairly well-preserved forest. We could also see the only gliding leaf frogs (Agalychnis spurrelli) of the trip. At dawn after the second night, we returned to the car and drove back the long way to San José, as Carlos' journey was now over and he had to get back to work. The other three survivors, however, would still continue for a few more days to another unexplored region of the country: the South Pacific.

20-22 July: Rancho Quemado

There is quite a long drive from San José to our destination in Osa Peninsula, so after leaving Carlos at the airport, we headed south until a hotel in Jacó, with a brief stop at sunset on the famous Tarcoles bridge to see the big crocodyles. In the hotel we had some beers on the pool, and get some rest to continue the journey the following day. We arrived to Rancho Quemado, in Osa, on the afternoon, with only a couple of stops for birdwatching and lunch. The reason to visit Rancho Quemado, very close to the famous Corcovado National Park, is to see what is perhaps Costa Rica's most emblematic snake, and one of the world's most legendary vipers. I refer, of course, to the black headed bushmaster or "plato negro" (Lachesis melanocephala). This species is endemic to the Osa Peninsula and its surroundings in the Costa Rican South Pacific, and until a few years ago it was practically impossible for foreign visitors to see them in the wild, as it is a very rare and elusive species that lives mainly in reserves or private lands that are difficult to access. However, in recent years a monitoring project is being carried out by the "Melanocephala project" which is studying this rare species in its natural habitat, thus allowing monitoring of the individuals and allowing foreign herpers to see them together with the project workers.

After contacting the project to book a morning bushmaster watching tour, they also arranged accommodation in a local house. The first day we simply settled in and tried to go for a walk in the evening. The problem here is that most of the land is private, so we were advised not to go on our own without booking a night tour with them, but we were still able to find some streams running through the forest to do some herping on our own, and see some species typical of this part of the country. The tour to see this legendary snake is not cheap, so Ivan, who is not as fond herper as Angel and I, decided that the next morning, while we went to see the viper, he would visit Corcovado NP with another local guide. It cost him a similar price and for him it was a better plan for seeing a greater diversity of species, so that's how we worked it out. Ángel and I would be picked up for the bushmaster tour and Ivan would take the car to the dock where he would be taken to the national park. And so we did, the next day, Angel and I met up with the trackers who are in charge of tracking the bushmasters. They do an incredible job, as day after day they go through the jungle through slopes and thick vegetation to locate the position of the individual, in this case an adult male. According to what they told us, the day before he was in a very exposed area, and that is where they took us. Although it was an accessible area for them, the large viper was well camouflaged among the lower floors in a steeply sloping area, a place we would never have looked at if we were herping there on our own. So we were able to enjoy, in situ, this extraordinary reptile. A pity that with the high humidity all the lenses of my reflex got fogged up, so I couldn't take very good pictures, but the important thing for me is always to see the animal. Going back, we could also see a new species of poison frog, the granular poison frog (Oophaga granulifera) and the strange water lizard (Centrosaura apodema). Due to the dry conditions, we failed to find the other poison frog in the area, ant the remaining costa rican species for me, the golfodulcean poison frog (Phyllobates vittatus).

When we returned to our cabin, the problems began. We met Iván there, who was supposed to be in Corcovado. Apparently, the guide told him that they were meeting in the morning at a dock that he would find by following the road straight through the village. As he did so, still at night, he saw that the road crossed a river that was not very fast-flowing, and since the guide told him that it was a good drive to get to the meeting point, and seeing no other alternative, he decided to cross it. With such bad luck that the car stalled and never started again. So we were left without a working car, in a village in the middle of nowhere and with no phone coverage. Here began a series of disagreements with the rental company, attempts to take advantage of our desperate situation by certain people in the village, and other bad things that I will not go into in detail. In short, we had to go to San José to get another car, and we lost two whole days of the trip that could be used to see more South Pacific species.

Black-headed bushmaster (Lachesis melanocephala)

23-24 July: San Vito

After changing cars, we left San José very late, so we spent the night on the way in San Gerardo de Dota, where we took the opportunity to see some birds, such as a couple quetzals, in the early morning before continuing on our way. We drove back to the Pacific as we had booked a tour to see another interesting and endemic species of viper, Porthidium volcanicum. Another species that was very difficult to see until a study and conservation project made things easier, in this case led by local owner Jose Luis Navas. However, we had no luck in the tour we did in the reserve and the target species did not show up, although we did see several terciopelos and some good-sized tarantulas. The next day, we stayed in the town of San Vito, where apart from enjoying the italian food, we would try to find the last viper target of the trip, the endemic Bothriechis supraciliaris. We went to an area recommended by several colleagues, such as Esteban and Max, and we walked through the forest for a while, finding the last terciopelo of the trip (making a total of 11, the trip's most seen snake species). Finally, we heard Ivan exclaiming "There it is!". And there it was, a beautiful adult female of good size with stunning blue-green coloration. One of those species that you don't expect to be so beautiful until you see it in person, and the perfect ending to our herping trip.

Blotched Palm-Pitviper (Bothriechis supraciliaris)

25-26 July: San Gerardo de Dota

Finally, the last night of the trip was spent again in the mountains of San Gerardo de Dota, where we were able to get better views of quetzals and other birds, such as the beautiful emerald tucanet. We were also able to see the specialties of Cerro de la Muerte that I had seen on my first trip, but were new to my trip mates, such as the red-footed salamander (Bolitoglossa pesrubra). At dusk we took a walk through the forest to try to find the last viper species of the genus Bothriechis for the trip, Bothriechis nubestris, as well as the other viper of the area, Cerrophidion sasai, but with no luck with either. And here our trip ended, tired but satisfied, watching the sunset from the beautiful mountains of Talamanca.

Conclusions

This has been my second visit to Costa Rica, and also to the tropics in general. This time, having a little more solvency and freedom by having a car has allowed me to explore the country in depth, traveling from end to end and seeing numerous species that I missed on my first visit. Among the herps I would highlight the fact that we saw practically all the tree vipers of the genus Bothriechis (except B. nubestris, which after all is practically identical to nigroviridis). In addition, we also saw numerous birds, up to 236 species. As both an avid herper and birder, I always find it difficult to find a balance between the two groups of animals on my trips, as the way of observing them in the wild is quite different. In Costa Rica, as I have explained throughout the report, the birds come out very early in the morning and the herps mainly at night, and seeing both is therefore very tiring as you hardly have time to sleep. Therefore, I want to thank my fellow trip mates for their understanding in this regard, with Iván who accompanied me in many "early morning birdings" and herped like a champion despite being less fond of herps, and Angel and Carlos who, without liking birds too much, joined in many birding moments. Costa Rica is always a country you will want to visit, with its tremendous biodiversity that makes that even having spent two months of full naturalism there, I still lack numerous species to observe. However, after this trip I think that the basics have been seen, and I am burning with the desire to travel to other tropical areas, especially in the Old World, which I have never visited, and I hope it can materialize soon. In the meantime, I hope that the people which have read this report have enjoyed the amazing Costa Rican biodiversity, and the most important thing, felt the need for its conservation. Rainforests are among the most threatened ecosystems on the planet, so it is important to take this into account and to support projects and local communities fighting for their conservation and that of the fascinating animal communities that inhabit them.

Herp Species List

Amphibians

Salamanders

Bolitoglossa presrubra

Frogs

Rhaebo haematiticus

Rhinella horribilis

Incilius melanochlorus

Incilius luetkenii

Incilius coniferus

Cochranella granulosa

Hyalinobatrachium fleischmanni (HO)

Hyalinobatrachium valerioi

Espadarana prosoblepon

Sachatamia ilex

Sachatamia albomaculata

Teratohyla spinosa

Hyalinobatrachium talamancae

Craugastor gollmeri

Craugastor mimus

Craugastor podiciferus

Craugastor fitzingeri

Craugastor crassidigitus

Craugastor megacephalus

Craugastor persimilis

Craugastor bransfordii

Craugastor noblei

Allobates talamancae

Oophaga pumilio

Oophaga granulifera

Dendrobates auratus

Diasporus diastema

Dendropsophus microcephalus

Dendropsophus ebraccatus

Agalychnis callidryas

Agalychnis saltator

Agalychnis annae

Agalychnis spurrelli

Boana rosenbergi

Duellmanohyla ruffioculis

Ecnomiohyla sukia (HO)

Trachycephalus vermiculatus

Hyloscirtus palmeri

Tlalocohyla loquax

Tripion spinosus

Scynax boulengeri

Scynax staufferi

Scynax elaeochroa

Smilisca baudinii

Smilisca phaeota

Engystomops pustulosus

Leptodactylus savagei

Leptodactylus poecilochilus

Hypopachus variolosus

Lithobates forreri

Lithobates taylori

Lithobates vaillanti

Istmohyla pseudopuma

Istmohyla picadoi (HO)

Istmohyla zeteki (HO)

Istmohyla lancasteri

Pristimantis cerasinus

Pristimantis caryophyllaceus

Pristimantis ridens

Reptiles

Crocodilians

Crocodylus acutus

Caiman crocodylus

Turtles

Chelydra acutirostris

Kinosternon scorpioides

Kinosternon leucostomum

Trachemys emolli

Trachemys venusta

Lizards and geckoes

Coleonyx mitratus

Thecadactylus rapicauda

Hemidactylus frenatus

Gonatodes albogularis

Lepidoblepharis xanthostigma

Abronia monticola

Mesoamericus bilobatus

Basiliscus basiliscus

Basiliscus plumifrons

Coritophanes cristatus

Anolis humilis

Analis oxylophus

Anolis tropidolepis

Anolis cupreus

Anolis limifrons

Anolis alocomyos

Anolis cf. pachypus

Anolis biporcatus

Anolis capito

Anolis lemurinus

Anolis frenatus

Anolis aquaticus

Anolis osa

Iguana rhynolopha

Ctenosaura similis

Sceloporus malachiticus

Sceloporus variabilis

Centrosaura apodema

Holcosus festivus

Holcosus undulatus

Aspidoscelis deppii

Aloploglossus plicatus

Snakes

Boa imperator x1dor

Chironius grandisquamis x2

Dendrophidion apharocybe x3

Leptophis nebulosus x1

Oxybelis brevirostris x5

Oxybelis koehleri x1

Trimorphodon quadruplex x2

Coniophanes piceivittis x1

Hydromorphus concolor x1

Dipsas articulata x1

Sibon anthracops x1

Sibon annulatus x3

Sibon longifrenis x3

Sibon nebulatus x2

Pliocercus euryzonus x1

Imantodes gemmistratus x1

Imantodes cenchoa x2

Imantodes inornatus x1

Phrynonax poecilonotus x1

Leptodeira nigrofasciata x1 x1dor

Leptodeira ornata x9

Leptodeira rhombifera x2

Lampropeltis abnorma x1

Enuliophis sclateri x1

Bothriechis lateralis x1

Bothriechis nigroviridis x1

Bothriechis schlegelii x6

Bothriechis supraciliaris x1

Bothrops asper x10

Lachesis melanocephala x1

Porthidium ophryomegas x2 x1dor

Porthidium nasutum x4

Micrurus nigrocintus x2

Micrurus mosquitensis x2

eBird trip report with the full bird list: https://ebird.org/tripreport/147626